Forword

Lynn Henderson is PCS National Officer (Scotland and Northern Ireland) and is Vice President of the Scottish TUC.

In April 2017, Unison’s Scottish National Secretary Mike Kirby told STUC conference:

“Democracy is never a finished job: whether it was extending the franchise to those without property, securing votes for women, or winning trade union rights, history tells us we make great progress and we have minor set-backs – but democracy is something we have to remake over and over again”

From their inception, trade unions have enabled workers to resist concentrations of power and wealth.

And today, trade unionists are increasingly clear that the structure of political institutions – and how they are composed – makes a fundamental difference to the balance of power in this country: namely, whether that system works in the interests of the many, or the few.

Most of us have known for a long time that there is something deeply wrong with the way Westminster operates. It has struggled to break away from its upper-class and empire-based past. Even when workers and trade unions had major victories in obtaining full franchise or workers’ representation in Parliament, the old and the new interests of wealth and power sought to find ‘workarounds’. They owned and controlled the media, they dominate and control the other institutions of power, parliament, civil service, banks and corporations, mostly run by people who thought and looked the same, educated at the same schools and universities. The way these institutions are designed and organised ensures that power is concentrated in small elite groups at the top. It is in their organisational DNA. This means that under any government, hierarchy and inequality are systemic – that is the Westminster system.

It’s obvious by looking at these institutions that they are exclusive: where are the representative numbers of women? Where are the ethnic minorities? Where are the workers?

The position of unions can have a fundamental impact on how our democracy and economy works. It was trade unions throwing their weight behind democratic reform that helped secure fair votes for elections in New Zealand in the 1990s.

Elections in the UK are increasingly unstable – with the system failing to deliver on First Past the Post’s central promise: ‘strong and stable’ government. Instead, time and again we have seen progressive majorities in this country over-ridden by the vagaries of a broken voting system: one in which votes are ‘split’ on the left, while millions of workers’ voices are thrown on the electoral scrapheap.

The way our politics works has changed almost beyond recognition. But one thing is increasingly clear amid the chaos: the establishment voting system is rigged against workers. Where Scotland’s proportional voting systems have encouraged political engagement and countered alienation, Westminster’s breeds apathy and distrust.

This report shows that getting rid of Westminster’s system offers huge opportunities for the union movement, with a new democratic system for a new economy. As the first two chapters show, PR works towards a consensual politics – where unions are included in government as key players. Instead, we have an ‘elective dictatorship’ and unchecked power.

A new democratic model is not only good for workers but social outcomes in general. As chapter three notes, countries which use PR have larger welfare states and lower rates of prison incarceration, and lower economic inequality. All of the EU countries which have embedded trade union rights, and have high union density and extensive collective bargaining coverage, use PR electoral systems.

Instead, under the Westminster system, we see resources disproportionally given to handful of swing seats – leaving large parts of the country to wither on the vine.

But Westminster’s system is skewed politically too: as chapter four notes, the UK constitution is increasingly rigged against the left. Labour would have been the largest party under Scotland’s Single Transferable Vote system in 2017.

Indeed, under proposed new boundaries, electoral bias against the left means the Conservatives will only need a lead of 1.6% to win a majority (less than they won by in 2017) – while Labour would need a lead of more than 8%.

Finally, we show that Westminster’s voting system is holding back gender equality. In the centenary of women’s suffrage, it is important to note that while the majority of union members are now women, the Westminster system is effectively locking them out of hundreds of closed-off ‘safe seats’ across the country – with the single-member nature of constituencies allowing men to ‘reserve’ seats without serious challenge.

From the calls of the Chartists, to pushing for devolution, unions have long been at the forefront of demands for a better democracy. Today, there is a new democratic frontier for trade unions in Britain: electoral reform.

There is increasing momentum for change within the union movement. How we get there is up for discussion, but one thing it clear: we cannot begin to build a ‘kinder, gentler’ politics without fair votes.

If we truly believe in the redistribution of wealth and power then the primary goal should be the sharing of power more equally. Only then is any transformation of the economy and society sustainable.

This is no small task, the powerful never share power willingly. Many of the rules of how our democracy works need changing. This report looks at the necessary but insufficient reform of our electoral system and the effect that would have on the outdated and deeply unequal institutions of government. But such a change would have greatest effect as a package of transformations. A whole system approach is required: the British state itself needs to be reorganised. We should make clear the road map. A Labour government can legislate for reform and a system of citizen-led constitutional conventions (as they have in Ireland) could propose the detail. It’s not simple, it’s not easy, but it is unavoidable if we wish to create a country governed by the many for the many.

I am proud to launch this report here in Scotland – now let’s extend this message across the UK and to the heart of Westminster.

Lynn Henderson

Political systems, structures and outcomes: Why the Westminster system is bad for democracy and society

The structures, powers and relationships of institutions are vital to understanding the ends that they generate. We cannot understand the outcomes of any political or social institution without, at least in part, understanding its institutional arrangements.

Politics then is, in many ways, about institutions: laws, courts, bureaucracies and the informal institutions of convention, social norm and practice. And sitting above all these institutions, right at the very top, is what we think of as the formal political system, which makes the laws, directs other institutions and sets public policy.

There are well known relationships between state institutions and outcomes – First Past the Post tends to lead to a two-party system for instance. But there are further implications for democracy and society that stem from our institutional arrangements.

This research explores the relationship between the Westminster model and politics in Britain. How our institutional arrangements affect the very society we live in; from levels of income equality to trade union rights; from the diversity of our representatives to the culture of politics in Britain today.

Models of democracy

In 1991, as he strove to advise newly democratising states of the old Eastern bloc on what constitutional designs to adopt, Professor Arend Lijphart outlined four types of democracy.1Lijphart (1991), Constitutional Choices for New Democracies, Journal of Democracy, vol. 2 (1), pp. 72-84.Presidential Parliamentarian Plurality Elections United States Philippines United Kingdom

Old Commonwealth

India

Malaysia

JamaicaProportional representation Latin America Western Europe

Those types were defined by two major constitutional decisions. Firstly, whether to use a presidential system, in which the state’s head of government is directly elected by the public, or a parliamentary system in which the head of government is the leader of the party (or group of parties) which represents most elected representatives.

The Westminster Model: power unchecked

Britain is the prototypical example of what Lijphart describes as the ‘Westminster model’.2Lijphart (1999), Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries, Yale University Press; New Haven. That model is defined by:

- The concentration of executive power in one-party and bare-majority cabinets

- Cabinet dominance

- A two-party system

- Majoritarian and disproportional electoral systems

- Interest group pluralism (in which interest groups, including trade unions, tend to exist in more of a free-for-all competitive environment).

- A unitary and centralised government

- The concentration of legislative power in a single chamber legislature or one with a very weak upper house

- Constitutional flexibility

- Absence of judicial review

- A central bank controlled by the executive.

Looking at British democracy in the Westminster model recalls the former Lord Chancellor Lord Hailsham’s comment that Britain is an “elective dictatorship” in which bare majority governments have almost unlimited power.

On the other end sits consensus democracy in which the converse of these features is true. However, it would be correct to think of most democracies sitting on a spectrum rather than as categories.3Ibid

Indeed, in the last two decades Britain might be seen to have moved along the spectrum closer to the consensual model. In large part this is because of constitutional changes initiated by the New Labour governments. Devolution has reduced Britain’s centralisation and the Bank of England has been made independent. Removing hereditaries from the Lords resulted in a small boost to its public legitimacy, allowing it to flex its muscles more often (though it remains a relatively poor check on the executive). While Westminster retains First Past the Post voting, new electoral systems have been introduced at other levels and Labour created a Supreme Court, energised by the Human Rights Act, able to issue advisory judgements. In addition, changes to voting patterns have brought two periods of hung parliament, weakening other aspects of the system.

Yet, at the same time, Britain remains a system in which disproportionate results abound, and Britain’s uncodified constitution means that with the right distribution of votes, a government can be elected on a minority of the vote with a sizeable parliamentary majority with which it may have carte blanche. This problem has been intensified by Brexit given that the EU’s laws provide a check on British government and the UK government’s desire to transfer much of the powers of these laws back as executive based ‘Henry VIII’ style powers is a reminder of the essentially majoritarian features of British democracy. Without a codified constitution, features such as the Human Rights Act also remain essentially in the gift of parliament, whereas in other states they would be entrenched so that super-majorities or other extra hurdles would be required to amend or repeal them.

Case Study: New Zealand, Westminster Style Government at Its Least Accountable

The pre-1993 system in New Zealand has been described as ‘the purest form of Westminster government’, with an uncodified constitution, a single chamber parliament and First Past the Post.

The 1978 and 1981 elections saw centre-right majority governments elected despite the National Party winning fewer votes than the New Zealand Labour Party. This government subsequently began a programme of unpopular neoliberal economic reforms. When Labour entered power, these reforms continued. The lack of inclusion of these reforms in manifestoes of both parties left New Zealanders with a feeling of distance from their leaders. Shifting to a proportional representation system was seen as a way of bringing honesty and accountability into New Zealand politics.

The system was changed to a form of PR known as Mixed-Member Proportional Representation (MMP) in 1996. The system produces highly proportional results while also maintaining a constituency link with 71 of New Zealand’s MPs elected on a First Past the Post basis and 49 elected from regional lists to ‘top-up’ representation for those parties who were previously denied their proportional share of seats.

This change resulted in a much more vibrant political eco-system. After a period in opposition NZ Labour returned to power in 1999, heading a coalition with the smaller, left-of-Labour Alliance Party. It subsequently governed for three more terms governing with support, de facto or de jure, from other parties.

These terms in office were marked by a repudiation of NZ Labour’s former neoliberal economic policies with Clark government policies including: the re-introduction of apprenticeships, Working for Families tax credits, interest-free student loans, setting up a publicly owned retail bank and pensions saving scheme (KiwiBank and KiwiSaver) through the New Zealand post office, record rises in the minimum wage, reduced rents for social housing, the nationalisation of an airline and the railways and new measures for climate change. There were also progressive social changes such as a new Supreme Court, civil unions for same-sex couples and legislation for smoke-free bars and restaurants.

PR is sometimes accused of causing political gridlock, but New Zealand Labour shows quite the opposite when a system truly represents citizens – it can galvanise change.

While Labour lost power in 2008, most of its legacy remained intact, with the centre-right National Party making a centrist pitch to voters.

It subsequently regained power in 2017, governing with support from the Greens and New Zealand First, a socially conservative party that is supportive of nationalisation and public spending.

The deals with these two parties include sizeable spending pledges on regional development, rail and the green economy, free counselling for the under-25s, elimination of the gender pay gap in the public sector, a new Green Transport Card to reduce public transport costs for those on low-incomes and welfare recipients, keeping the superannuation age at 65, and raising the minimum wage from $15.75 to $20 an hour by 2020.

This reflects how the ‘centre’ can shift in favour of workers when consensual politics replaces a polarising, majoritarian model.

Consensus Democracy and Corporatism: Why the Westminster system is bad for trade unionism

One of the dimensions of Lijphart’s majoritarian vs. consensus democracy scale is interest group pluralism vs. corporatism.

Interest group pluralism refers to a system in which interest groups, such as employer groups and trade unions, are competitive and uncoordinated. Corporatism is an interest group model in which groups are organised into national, specialised and hierarchical organisations, with those groups included in the policy making process,4Lijphart and Crepaz (1991), Corporatism and Consensus Democracy in Eighteen Countries: Conceptual and Empirical Linkages, British Journal of Political Science, vol. 21 (2), pp.235-246. often so directly as to bypass parliament altogether, acting as an additional leg of the policymaking process.

The UK is generally held to rank towards the pluralist end of this scale, though there have been sporadic examples of corporatist practice such the 1970s social contract.

Two variables tend to describe the level of corporatism in a state according to Lijphart’s research: the level of participation of left wing parties in a government and the level of consensus democracy. Britain underperforms on corporatism despite the number of years it has been governed by a left-of-centre party, and this is connected to its majoritarianism.

The connection between corporatism and consensual democracy may seem unclear but Lijphart views it as the extension of a principle of consensus making to the economic sphere. Of course, this may also be cultural, but the relationship between political culture and political institutions is not one way, but rather circular with both creating and replicating each other.

Looking to the German economic systems, Labour under Miliband’s leadership adopted what is seen as truly ambitious in political economy terms,5Bale, T. (2015) Five Year Mission: The Labour Party under Ed Miliband, Oxford University Press, Oxford. the aim to shift the British economy from what the eminent political economist David Soskice called a liberal market economy to a coordinated market economy notable for lower inequality, higher industrial output, strong vocational training and strong unions.

However, states such as these require a degree of public economic consensus making and ultimately a more consensual political model.

Majoritarian government and the erosion of trade union rights

The Westminster model (associated with one-party-takes-all, First Past the Post electoral systems) is noted for giving carte blanche to governments elected on a small proportion of the vote. In this way, majoritarian government can work against policy stability, creating a seesaw effect on legislation. Lacking the need to build coalitions of support around policy change, single-party governments can rapidly undo the work of previous governments. As one majority party leaves office, the next rides in with a commitment to undo the work of the previous government. The electoral system, and the political culture it encourages, incentivises parties to create sweeping reforms, setting a new policy direction and even going further and faster in the opposite direction. Nowhere is this more evident than in legislation affecting trade unions.

Law on trade unions in Britain is frequently described as the most restrictive in the western world. As the pendulum of majoritarian government swings between parties, trade union rights have been the target of sweeping reforms.

Over the last forty years successive UK governments have played tug of war with the rights of trade unions. The list of statutory obligations on unions has grown exponentially as majority governments (some with significant majorities) have sought to restrict and heavily regulate trade union activity.

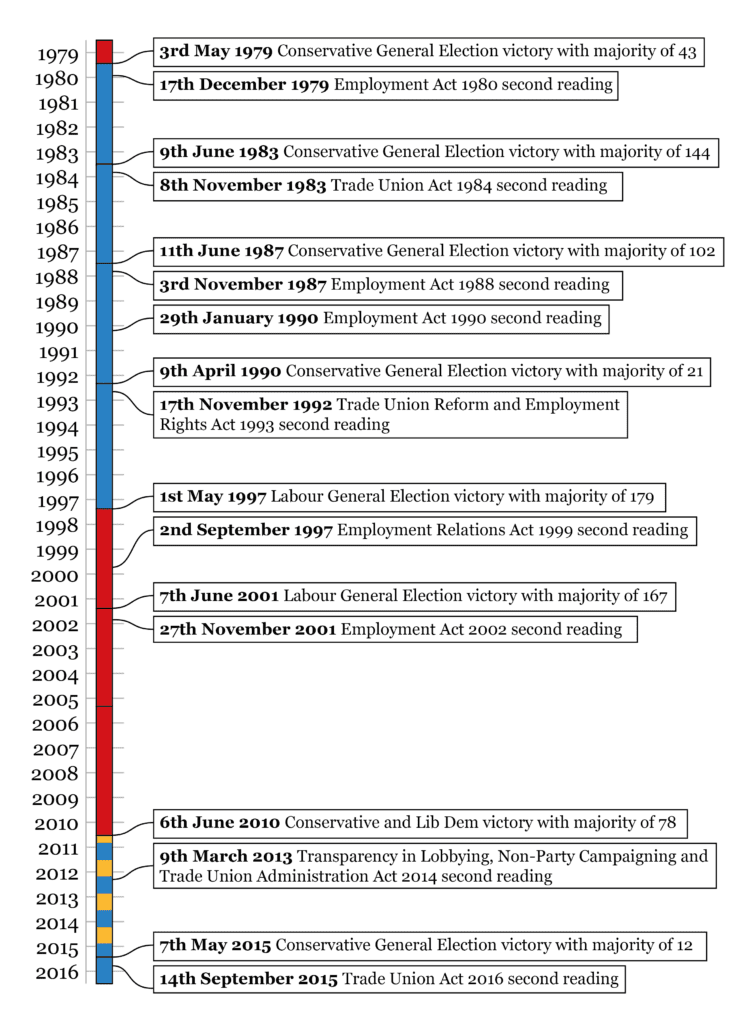

Since 1980 there have been no less than 14 employment and trade union acts restricting and then, to a degree, clawing back union rights. Below we chart the seesaw in trade union rights against the change in majority governing party.

The graph highlights the employment acts that have gone the furthest in putting statutory requirements on union activity.

We can see that many of these acts, in particular the Employment Acts of 1980, 1988, Trade Union Acts of 1984 and 2016, and the Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Act 1993, have been introduced swiftly after General Elections. In all cases the legislation has reached second reading less than seven months after the election.

From removing union immunity in 1982 to changes to political funds in 2016, the pendulum of majoritarian government has worked against union interests. There is a clear contrast here between the Westminster model and democracies in the consensus model such as New Zealand (post 1993), Germany and the Nordic states.

PR and trade unionism

Union membership has been falling across most countries in recent years. But the UK has experienced particularly steep declines since 1979. Union membership has fallen from over 13 million in 1979, to just over 6 million in 2016. The steepest decline occurred in the first two decades of this period.

Of all EU countries the UK has the fourth lowest proportion of employees covered by collective bargaining. Whilst countries such as France, Belgium, Austria, Finland, Portugal, Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark have levels upwards of 80%, in the UK, collective bargaining coverage stands at just 29% (the EU average is 60%).

| No. | Country | Covered by collective bargaining (%) | Level of collective bargaining | Electoral system for national legislature (family/system) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | France | 98% | Industry and company | Majority (two-round) |

| 2 | Belgium | 96% | National (sets framework) | PR (List PR) |

| 3 | Austria | 95% | Industry | PR (List PR) |

| 4 | Finland | 91% | National | PR (List PR) |

| 5 | Portugal | 89% | Industry | PR (List PR) |

| 6 | Sweden | 89% | Industry – much left to company negotiations | PR (List PR) |

| 7 | Netherlands | 84% | Industry (also some company) | PR (List PR) |

| 8 | Denmark | 80% | Industry – much left to company negotiations | PR (List PR) |

| 9 | Italy | 80% | Industry | Mixed (parallel)* |

| 10 | Norway | 73% | National and industry | PR (List PR) |

| … | ||||

| 26 | UK | 29% | Company | Majority (FPTP) |

| Average (EU) | 60% |

Data on collective bargaining drawn from www.worker-participation.eu which covers 28 EU member states plus Norway.

The countries with the highest levels of collective bargaining coverage have high levels of union membership or legal structures that give collective agreements significantly wide coverage. In the UK, as with other countries at the bottom of the table, company level rather than industry level bargaining is dominant.

In terms of union density, the UK is around the EU average but countries such as Finland, Sweden and Denmark have almost three times this level.

| No. | Country | Trade Union density (%) proportion of employees in union | Electoral system for national legislature (family/system) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Finland | 74% | PR (List PR) |

| 2 | Sweden | 70% | PR (List PR) |

| 3 | Denmark | 67% | PR (List PR) |

| 4 | Cyprus | 55% | PR (List PR) |

| 5 | Norway | 52% | PR (List PR) |

| 6 | Belgium | 50% | PR (List PR) |

| 7 | Malta | 47% | PR (STV) |

| 8 | Luxembourg | 41% | PR (List PR) |

| 9 | Croatia | 35% | PR (List PR) |

| 10 | Italy | 35% | Mixed (parallel)* |

| … | |||

| 14 | UK | 26% | Majority (FPTP) |

| Average | 24% |

Data on union density drawn from www.worker-participation.eu which covers 28 EU member states plus Norway.

Not all countries with high union density have high collective bargaining coverage. France actually has lower levels of trade union density than the UK, and is also the only other country in the EU to use an electoral system which isn’t proportional. Industry-level agreements there cover most workers but often provide minimum terms.

Indeed, all of the EU countries which have embedded trade union rights, and have high union density and collective bargaining coverage, are democracies which employ PR electoral systems.

PR and politics of the left: Why PR is good for social outcomes

PR famously tends to lead to coalition governments. But it is worth considering the form of those governments and what their effects are.

There is evidence that countries with PR tend to elect more left-wing governments than countries with majoritarian electoral systems such as First Past the Post. Research by Iversen and Soskice,6Iversen and Soskice (2006) ‘Electoral Institutions and the Politics of Coalitions: Why some democracies redistribute more than others’, The American Political Science Review, vol. 100 (2), p.165 for instance, indicates that left-of-centre governments are formed more frequently under PR governments than right-of-centre ones.

Iversen and Soskice argue that in a society with three groups – left, middle, right – where the left has a preference for a larger state and redistribution and the right has a preference for a smaller state and tax cutting, the middle will principally be made up of those who benefit from some redistribution which they prefer to keep and also from lower taxes.

In a two party electoral system this middle become swing voters who have a choice between giving power to the right or the left. Iversen and Soskice argue that the logic hence becomes (assuming the two are equally distant from the centre) to prefer the right to avoid potential taxation by the left, but in a PR system the middle can form its own party with the choice to form government with the left or right. In this case the middle party’s best strategy is to work with the left because together they create a strongly redistributive state without undermining their electoral base, for example by taxing the wealthiest.

Iversen and Soskice argue that an exception such as Germany, where the centre-right dominates, is due to the centre-right’s much closer position to the centre, and it’s worth remembering that the genesis of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany was in a desire for a kinder faced ‘conservatism with a heart’ as a departure from the pre-1948 right.

The form of government in consensus democracies may also encourage more progressive ends in and of themselves. Research from Lijphart (explored in more detail below) shows that democracies with more consensual structures have more progressive ends on a range of measures – such as a large welfare state, more money on foreign aid and lower rates of prison incarceration. There is also a multitude of studies that point to consensual democracies being more equal economically.7Lijphart, Patterns of Democracy. Verardi (2005), Electoral systems and income inequality. Zuazu (2017), Electoral Systems and Economic Inequality: A Tale of Political Equality

The logic of this is intuitive: different parties have different electorates to satisfy and a broader coalition, dependent on a broader range of support, must satisfy a broader electorate – the result of involving more parties is greater demand for more spending. The post-2017 General Election in the UK is a good example of this. Whilst austerity has continued, the ability of the DUP to negotiate with the UK government led to increased spending for Northern Ireland.

The key difference in the UK experience compared to PR systems is that hung parliaments in the UK will tend to advantage negotiations with parties with defined geographic bases. This means the money is often spread on the basis of geographic concerns whereas in a PR system other groups and interests can achieve recognition more easily.

Case Study: Scandinavia, Consensus Democracy

Consensus was embedded deeply throughout Scandinavian societies and politics after the ascent of social democratic parties in the pre-war era. Corporatist practices were deeply embedded.

Politically the period between the mid-30s and 70s saw a hegemonic position for Scandinavian Social Democratic Parties. But they did not use this position to drive through change alone. Instead, Social Democratic parties saw themselves as governing for the whole nation. The Scandinavian tradition of negative parliamentarism – in which parties are asked to vote against a government rather than for a government – enabled the Social Democrats to find consensus with the opposition, rather than rely on their usual support party. Typically, they would work with the Centrist or Agrarian parties, unique Scandinavian parties who represent farmers and whose ideology is highly decentralist, tending to lead to the decentralised features of the Nordic states.

By gaining support across the political system for proposals, the Social Democrats embedded their policies in wider politics. Even when Social Democrats gained majorities (as they won in Norway in four elections from 1945 until 1957 and Sweden in 1961) the parties made special efforts to be inclusive.

With time, the parties become the largest parties among a diverse left, as part of a broad progressive landscape – although in the three Scandinavian states a sort of ‘bloc politics’ has evolved, which pitches Social Democratic allied parties against the ‘bourgeois’ parties for parliamentary majorities.

This embedding has helped contribute to large parts of the Nordic model remaining intact, with the Nordic centre right often embracing the language of workerism in an attempt to win power and, while weakened, the primary features of the Scandinavian model remain in place.

While bloc politics has made Scandinavian politics more majoritarian, governments and parties still work across the political spectrum. Parliamentary committees remain extremely powerful in Scandinavian politics and some are dominated by standing coalitions such as the European Affairs Committee in Denmark, famous across the EU for its strong powers. The committee is dominated by consensus forming among the ‘traditional’ four parties of the Social Democrats, agrarian-liberal Venstre, Conservatives and left-liberal Radikale. There has also been cross-bloc cooperation over budgets and welfare policy in Denmark, weakening the current centre-right government’s cuts.

The broad, inclusive political environment created by a consensus democracy has protected the legacy of social democratic governments and still serves to aid progressive causes. The dominant political strategy still largely favours progressive causes.

Distributing public funds and marginal seats

A ‘safe seat’ culture is embedded in the Westminster system. In campaigning terms this means parties have an incentive to focus only on those constituencies they perceive as winnable – the marginals. Research shows that candidate campaign spending varies massively depending on the marginality of the constituency. The amount of money spent on winning a single vote varies between £3.07 and just 14p.8Terry (2013) Penny for Your Vote, Electoral Reform Society, London In a similar way, the marginality of a seat can distort public spending.

Ministers have discretionary power to target state resources at particular projects and particular areas. The problem of ‘pork-barreling’ is well established – local politicians in certain political systems can use their positions on committees to leverage government funding for their own constituencies (the negative side to the constituency link). But there is also the opportunity for ‘top-down’ bias in distribution decisions.

The safe and marginal seat culture created by First Past the Post generates an incentive for governments to direct public funds at a handful of winnable seats rather than towards where the need is greatest – especially when close to an election. It seems obvious that, given the choice, the party of government would choose the safe over the marginal seat when it comes to closing down hospitals or making other unpopular spending decisions, but it is also borne out in research.

Academics have measured the relationship between constituency marginality and grants to English local authorities.9Ward and John (1999) Targeting Benefits for Electoral Gain: Constituency Marginality and the Distribution of Grants to English Local Authorities, Political Studies, Vol 47, Issue 1, pp. 32 – 52 They looked at central government grants to English local authorities in the financial year 1994/95 (long enough after the election for the government to target spending and for that spending to accumulate and be perceived by the electorate before the next election). They found:

“The government allocated around £500 million more to local authorities containing marginal constituencies and around £155 million more to ‘flagship’ local authorities than they could have been expected to get on the criteria of social need and population.” (Ward and John, 1999)

Academics at the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE looked at the relationship between marginal seats and hospital closures between 1997 and 2005.10Nicholas Bloom, Carol Propper, Stephan Seiler and John Van Reenen (2010), The Impact of Competition on Management Quality: Evidence from Public Hospitals, CEP Discussion Paper, May 2010, Paper No’ CEPDP0983. This was part of a wider piece of research on competition and management practices in the NHS. They found a relationship between areas with marginal seats and fewer hospital closures:

“Marginality in 1997 has a significant positive impact on the number of hospitals that exist in 2005” (Bloom et. al., 2010)

In other words, hospitals in marginal constituencies were less likely to close down.

Whilst the research in this area is not extensive, there are clear incentives to favour the logic of political economy over need when making spending decisions within a safe seat culture. This logic is not completely absent under different systems but is certainly accentuated under First Past the Post.

The Westminster voting system is also used at the local government level in England and Wales and has created over 100 councils with no political opposition.11Electoral Reform Society (2013) https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/campaigns/local-democracy/ A lack of political opposition creates an environment free of scrutiny and this can have a real impact on the use of public funds.

Councils dominated by single parties could be wasting as much as £2.6bn a year through a lack of scrutiny of their procurement processes.

Research looking at the savings in contracting between councils dominated by a single party (or with a significant number of uncontested seats), and more competitive councils finds that ‘one-party councils’ could be missing out on savings of around £2.6bn when compared to their more competitive counterparts – most likely due to a lack of scrutiny of contracting processes.12Fazekas (2015) The Cost of One-Party Councils, ERS, London £2.6bn is a lot of potential extra cash for struggling authorities, which could be put towards infrastructure, housing investment or better pay for in-house council staff – rather than subsidies to unchecked private companies.

The report also measures councils’ procurement process against a ‘Corruption Risk Index’ – and finds that one-party councils are around 50% more at risk of corruption than politically competitive councils. Needless to say, it is not workers who benefit from this, but far more frequently major outsourcing firms and private developers.

Kinder, Gentler Democracy

Before Jeremy Corbyn advocated a ‘kinder, gentler’ politics the term had already been used in reference to consensus democracies which Lijphart argued are ‘kinder, gentler’ democracies.

Lijphart’s Patterns of Democracy is an attempt to do two things.13Lijphart (1999) Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries, Yale University Press; New Haven. First, he seeks to classify, and evaluate consensus democracy as opposed to the majoritarian type. Then he asks, ‘so what?’, seeking to evaluate the ends that consensus democracy produces.

Using rigorous statistical testing Lijphart finds in favour of the view that consensus democracy has a higher democratic quality in several areas: higher turnout, lower perceived corruption, higher satisfaction with democracy, and a closer proximity between voter and government in terms of policy preferences. These findings are replicated across the academic literature.

Lijphart also finds lower rates of inflation and unemployment, higher spending on welfare and social programmes, energy efficiency, lower rates of prison incarceration, and higher foreign aid spending in consensus democracies. He also finds lower levels of economic inequality which he associates with higher political equality.

Clearly a role for culture and history must be included in any understanding of a country’s politics, but political institutions and cultures interact – meaning these close correlations cannot be ignored.

PR and left-of-centre politics in the UK: Why First Past the Post is a hindrance for Labour

In the United Kingdom general election of 2005 the Labour Party won 35% of the vote. As a result, it won 355 seats, 48 down from 2001 – but still enough to give it a sizeable majority of 66.

It had beaten the Conservatives by a mere 3%, but this was enough to deliver it 157 extra seats. Critics of the electoral system will, of course, comment that such results are unfair.

Five years later the Conservatives won 36% of the vote. They would beat Labour by 7%, but the electoral system would only deliver them 306 seats, 48 more than Labour, forcing the Conservatives into coalition with the Liberal Democrats.

Yet the advantage Labour enjoyed in the electoral system through the years of the 2000s has been whittled away and reversed in the 2010s. Labour gained more votes than the Conservatives in 2015, going up 1.4% in votes as opposed to 0.8% for the Conservatives – yet they lost 26 seats while the Conservatives won their first majority government in 23 years.

Labour’s tremendous unexpected success in 2017, where it gained nearly 10% of the vote winning its highest vote share in 16 years and running the Conservatives within 2.5%, saw a return of only 262 seats – 4 more than in 2010.

This section will look at the mechanics of the electoral system in more detail, and how it might help or hinder Labour in the future.

Electoral Bias

Electoral bias is an inevitable feature of any electoral system which features constituencies (this includes PR systems which also feature constituencies, though they will typically have less of it). During the 2000s the Conservative Party became deeply concerned with electoral bias, without fully understanding it, leading to a poorly designed boundary law in 2011.

The Conservative explanation of electoral bias – that it was due to unequally sized seats, is only part of how electoral bias works in practice, as the country’s leading experts on electoral bias and electoral geography such as Ron Johnston, Charles Pattie, and Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher have demonstrated.14An excellent summation of the causes of bias from Johnston and Pattie can be found at http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/electoral-bias-in-the-uk-after-the-2015-general-election/

First it’s important to note the vital different between bias and disproportionality as the two are often conflated.

Disproportionality is where sizeable differences exist in the vote percentage and the percentage of seats won. For instance, a result where a party wins 36% of the vote but 51% of the seats is clearly disproportionate.

Bias is where an electoral system produces the same result regardless of how proportionate that result is. For instance, if two parties win the precise same number of votes, but one party wins more seats than the other, that is bias.

Such bias can result in ‘wrong winner’ elections as in 1951 when Labour won the most votes (48.8% vs. 48.0% for the Conservatives) but the Conservatives won a parliamentary majority.

And indeed, recent projections based on opinion polls from the website Electoral Calculus have confirmed that this remains a possibility for the next election, with Electoral Calculus projecting that on 40.7% of the vote for Labour to 40.5% for the Conservatives, Labour would still lag 18 seats behind the Conservative Party.15More at: https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/more-votes-but-less-seats-surely-youre-joking/

Four main elements cause electoral bias, all caused by the interaction between the spatial spread of votes and the electoral system.

Constituency size effects. This is where constituencies which have fewer voters in them tend to lean in one direction. Several elements cause this bias – for instance, Wales being purposefully overrepresented, population movement or simple bad luck. This is, in fact, one of the weaker causes of bias but it is highlighted first here due to its outsized national attention.

Abstention bias. Constituencies are supposed to be drawn on the basis of electorate sizes (that is all those eligible to vote) rather than the numbers of voters (those who actually turn out). Hence, where there is a mismatch between voters turning out in one party’s constituency and in another, this will create bias. Typically, in Britain, turnout is lower in Labour constituencies.

Third Party bias. This has two elements. Firstly, if a third party wins a seat where a major party does well, this will produce a bias against the major party, as those votes will be wasted. Alternatively, if a third party tends to do better in seats where a major party does well, but not well enough to defeat the major party, then it will produce a bias in favour of the major party. For most of the post-war period this has tended to result in an effect where third party votes tend to favour the Conservatives, but third party seats have tended to favour Labour because the third party was the Lib Dems (or that party’s predecessors) and the Lib Dems tended to do better in Labour areas. In 2015 however, the third party in seats become the SNP and the third party in votes become UKIP (though this did not last until 2017) and this produced a sharp shift in the effect of the third-party bias, making it markedly pro-Conservative.

Efficiency bias. In a First Past the Post election it is most ‘efficient’ to spread out your vote in such a way that when you win constituencies you do it by a small margin, whereas when you lose a constituency you do it by a large margin – this minimises wasted votes. New Labour had an extremely efficient vote spread because where it did not win it was often far behind the Conservatives and even in third place to the Liberal Democrats. Compared to ten years ago Labour’s vote spread has become less efficient as voters across the UK have polarised. Labour has begun stacking up impenetrable majorities in its safe seats (such as the 77.1% in Liverpool Walton), which, while satisfying, do not help the party gain power.

We can look at bias by asking ourselves what would happen if there were a uniform national swing in different directions. Assuming a tied vote, the Conservatives would be largest party by 12 seats. Labour would need to do 0.8% better than the Conservatives to become largest party and would need a lead of 7.4% to win a majority compared to 3.4% for the Conservatives.

This problem would be exacerbated if new boundaries were introduced, which on their current form would increase the bias as such that the Conservatives would need only a lead of 1.6% to win a majority (less than they won by in 2017) and Labour would need a lead of 8.2%. Labour would need to be 3.9% ahead to become the largest party, even though seats would be more equally sized, due to the effects of other parts of the boundary law, but more importantly, the spatial spread of Labour’s vote.16Stats in this and previous paragraphs from Anthony Wells of YouGov and UK Polling Report, available at: http://ukpollingreport.co.uk/blog/archives/9951

Labour voter coalitions

Party support must be broad in a majoritarian democracy like the UK – broad enough to win enough voters in enough seats to win the balance of an election. Having more voters is obviously beneficial, but if those voters are poorly distributed it will not aid the party.

Labour’s historic coalition was, of course, principally the working class, in combination with a sliver of the left-wing intelligentsia. This alliance can be seen in the alliance of trade unionists and Fabians who drove the party’s formation.

Economic and social changes, however, changed this mix. Socially, a more educated population enlarged the number of middle class voters embracing so-called post-materialist views, leading to the New Left of the 1960s. This led to the Third Way of the 1990s. The political scientist Gerassimos Moschonas said it best when he said that Third Way social democracy was at one and the same time closer to the centre economically while also more embracing of New Left issues such as multiculturalism, the environment and gay rights.

New Labour actually gained support among the working class compared to 1980s Labour during its initial outings though lost more from this group than its middle class support during the years ahead. Labour also seemingly became more middle class in 2015, and the tie between education and result in 2017 led some to overclaim that Labour had become a ‘middle-class’ party.

It is commonly stated that the white working class, are being drawn towards the populist right – many talk now of a ‘Left Behind’ group drawn towards UKIP and other populist forces. Political scientists such as Eric Kauffman have argued that “It’s NOT the economy, stupid” and that recent events such as Trump and Brexit are principally driven by values. The Left Behind are commonly misunderstood as Left Behind economically, but are also Left Behind when it comes to cultural shifts. They are older voters who struggle economically and culturally with a socially liberal, diverse, increasingly global nation.

Yet this version of events fails to note from where it is that values originate. Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker have demonstrated that the Labour vote is connected to those areas with employment in cosmopolitan industries, with large numbers of people in bad health and large numbers of the ‘new working class’ of the precariat, those who work without predictability or security.17Jennings and Stoker (2016) The Bifurcation of Politics: Two Englands, The Political Quarterly, vol. 87, 3, July-Sept 2016. Jennings and Stoker (2017) Tilting Towards a Cosmopolitan Axis? Political Change in England and the 2017 General Election, The Political Quarterly, Vol. 88, 3 July-Sept 2017.

They argue that these experiences drive cosmopolitan values, as do expanding university education, mobility and multiculturalism, in addition to the familiar emerging patterns of age and education. What emerges therefore is a complex patchwork, where those who are often experiencing economic insecurity of one type are pitted against those experiencing new-found cultural insecurity.

But while this latter group of older working-class voters is poor, they do not necessarily have the same kind of insecurity, having stable (albeit very low) incomes from pensions and more secure housing and tenancies than those from a younger generation. This is a new class divide, tied strongly to security, which intersects with age, education and values – rather than purely geography. This disconnect weakens Labour’s electoral prospects.

This divide can be seen in the 2017 General Election results in which, whilst the predictions of disaster did not pan out, Labour did in fact lose six seats to the Conservatives: Derbyshire North East, Mansfield, Middlesbrough South and Cleveland East, Stoke-on-Trent South, Walsall North and Copeland (which the Conservatives had taken in a by-election earlier in 2017). These seats had been leave voting areas of post-industrial decline, impoverished, poorly educated and older.

Labour’s gains however were in younger more educated areas, often in university seats such as Canterbury, Plymouth Sutton and Devonport, Portsmouth South, Battersea and Brighton Kemptown.

While Labour’s 2017 saw an excellent performance for Labour, the geographically-focused nature of First Past the Post appears to be harming the party – with Labour’s vote rising but not necessarily in seats where it is most needed.

In this sense, the fact that seats do not match regional or national vote share under Westminster’s system could become an increasing hindrance for Labour – particularly if it is close to maxing out the younger, progressive voters that backed it in 2017.

However, after the 2017 election, the Electoral Reform Society projected the result of the election under three alternative electoral systems – the non-proportional Alternative Vote, as well as the proportional Additional Member System (used in Scotland and Wales) and Single Transferable Vote (used in Northern Ireland and the Republic).

In these projections – where people were also asked if they would vote differently under these systems – the Society projected that Labour would have won 286 seats under AV, 274 under AMS and 297 under STV, up from 262.

It may seem odd for Labour to increase its seats under other systems but Labour actually won around its proportional share of seats (40%) in 2017 – while the Conservatives unfairly benefited from the broken system, winning 42% of the vote but 48% of the seats. This difference can be explained by changes in voting pattern and preference flow.

A change in electoral system need not hinder Labour electorally – in fact, given the increasing electoral bias towards the Conservatives, it may well be an essential shift for progressives.

Winning the next election

In order to win an absolute majority at the next election, Labour will need to win an additional 64 seats. This is more than twice Labour’s net gain of thirty at the 2017 election.

There are two ways that Labour could win the next election: Labour gaining votes, or the Conservatives losing them. This may seem obvious, but it is important to unpick.

A key question Labour needs to consider is how ‘hard’ the Conservative vote looks. In the fallout from the election it is often easy to forget that the Conservatives made substantial gains as well as Labour. Both parties won more than forty percent of the vote for the first time since 2001 in Labour’s case and 1992 in the Conservative case. Polls since the election show the core Conservative vote is surprisingly robust given everything that has happened since, with a high floor of around 37-38%. While the lessons of the last few years should indicate that things can and do change, it would be unwise of Labour to count on a decline in Conservative vote going forward.

Hung parliaments and regional polarisation

The last three elections have seen two hung parliaments and a very thin majority. An increasing preponderance of hung parliaments has been predicted by political scientists for some time. The very first academic article Professor John Curtice wrote, for instance, suggested that eventually a parliament would be produced in which a Northern Irish party is the government decider: the result we saw in 2017.18Curtice & Stead (1982), Electoral Choice and the Production of Government: The Changing Operation of the Electoral System in the United Kingdom since 1955

The most commonly cited reason for this is the rising support that third parties enjoyed through most of the post-war period. Of course, that support was reduced in 2015 and 2017 as the Liberal Democrats collapsed, but nonetheless third parties hold a historically sizeable number of seats between 12 remaining Lib Dems, 35 Scottish Nationalists, 4 Plaid Cymru, a Green and the 18 seats of Northern Ireland – all of which are completely uncompetitive for major parties.

It is notable that fully 57 of these 69 seats are held by parties (and one independent in Northern Ireland) who are very geographically focused. First Past the Post rewards strong regional parties and makes them harder to shift. The bulk of these seats are SNP and whilst the Nationalists did lose seats in Scotland at the 2017 election (and many more came into target range,) SNP polling in Scotland has not noticeably worsened since the election.

However, there is a second explanation for the increasing preponderance of hung parliaments – polarisation. John Curtice suggests polarisation has reduced the number of Labour/Conservative marginal seats required to make majorities possible.

Labour in a Hung Parliament

The increasing preponderance of hung parliaments could however be positive for Labour. Labour is easily advantaged in most hung parliament scenarios because the bulk of third party seats – SNP, Plaid Cymru and Green are held by parties whose natural preference is not only for Labour but who would suffer strategically for not backing a progressive government. The Lib Dems too, seem likelier to back Labour as the Conservative stance on Brexit makes cooperation similarly impossible for the pro-European party.

If this seems unusual it is worth remembering that the norm in Labour’s history has actually been to struggle to win and maintain working majorities. Labour has only been re-elected to a working majority twice – in 2001 and 2005. The pre-war Labour governments were minority affairs, Clement Attlee only secured a majority of 5 seats in 1950, Harold Wilson won a majority of only 4 in 1964, forcing him to seek a fresh mandate in 1966, while the Callaghan government worked in the context of a hung parliament, where Labour needed to work with other parties.

But these governments still attained real, solid gains with real meaning for working people, though they were often short-lived in office. And, as noted before, the policy seesaw created by a majoritarian system and lack of consensus building in our politics means these gains can be easily reversed.

In addition, the voting system far more frequently locks the left out of power. Analysis by Make Votes Matter has shown that in 14 of the past 15 elections pre-June 2017, there has been a ‘progressive majority’ among voters.19LCER & Make Votes Matter (2017), The Many Not the Few Yet the electoral fragmentation of the left – compared to the relative partisan unity of the right – means that progressives are frequently denied government, due to a voting system which ‘wastes’ all votes for those other than the first-placed candidate in each seat – even if the majority voted for left-of-centre parties.

A conversation about proportional representation would help Labour have a more productive relationship with smaller parties and allow it to institute long running changes to the functioning of British democracy which would be more inclusive, driving long running changes in the way decision making in Britain is done and promoting progressive ends.

General Election 2022 – summary

In summary, the hurdles facing Labour in achieving a majority at the next election are considerable. The changing electoral bias in the system now means Labour needs a significant lead over the Conservatives to win the next election. After the boundary changes, Labour may need five times the percentage lead to get a majority in Parliament. The increasing concentration of the Labour vote, the impact of SNP and UKIP as third parties in seats and votes as well as boundary changes make a Labour majority a much harder target. And it is worth remembering that working majorities for Labour in the past have been hard to achieve.

Social and economic changes have vastly shifted Labour’s base. New class divides, tied strongly to security, age, education and values see Labour support coming from younger and more educated groups. These groups are increasing but it is likely that this support is more fluid and the change in demographics not swift enough to have a significant impact on the next election.

In order to win an absolute majority at the next election, Labour will need to win an additional 64 seats – more than twice Labour’s net gain of 30 at the 2017 election – in the face of these difficult electoral circumstances.

As analysis of the 2017 General Election shows, we have not returned to two party politics.20Garland and Terry (2017) The 2017 General Election: volatile voting, random results. Electoral Reform Society; London Third party seat share is high and hung parliaments are likely to continue to be a feature of UK politics. But Labour has an opportunity to benefit from this future with the right strategy and openness to reform.

If the system now consistently works against Labour – it may be time to consider changing it.

PR and inclusion: why the Westminster system is bad for equality

With the majority of union members now women – and with unions leading the way in opposing the gender pay gap – equality is a core focus for the labour movement.

As TUC General Secretary Frances O’Grady has noted,21https://labourlist.org/2018/03/frances-ogrady-how-to-use-trade-union-power-to-support-women/ we must “keep using the power of our trade union movement to support women in their workplaces, taking action wherever inequality and harassment occur, and working to stop it happening in the first place.

“It’s what women trade unionists have been doing for two centuries – and we’ll keep going for as long as it takes.”

As trade unions are actors in the political sphere as well as the workplace, that struggle must extend to our political institutions – ensuring women’s voices are not marginalised but are instead at the centre.

However, Westminster’s voting system is holding back equality in our institutions as well as skewing our economy.

Diversity in Westminster is improving at a glacial pace. If women’s representation in parliament improved at the same rate as it did at the last General Election it will be 2062 before we reach equality.22Fawcett Society (2017) ‘Women’s Representation in Parliament stalls at 32% after General Election 2017’ https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/news/

Research shows that gender equality in Parliament is being held back by Westminster’s voting system, with dozens of seats effectively ‘reserved’ by incumbent men.23Electoral Reform Society (2018) https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/latest-news-and-research/media-centre/press-releases/international-womens-day-parliamentary-seats-across-england-are-effectively-reserved-by-men-research-shows/ Of the 212 currently-serving MPs first elected in 2005 or before, just 42 (20%) are women. In contrast, of the MPs remaining who were first elected in 2015, there is near gender parity – 45% are women.

The prevalence of ‘safe seats’ under Westminster’s voting system, means that once a seat is in an MP’s hands, it may be theirs for decades. At the last election only 99 of the 650 seats changed hands. This means despite measures to improve the number of women candidates, the number of winnable or marginal seats that could possibly change are limited.

Systems with proportional electoral systems are generally more representative. The top ranked democracies in the world for women’s representation – the Nordic states, Mexico, South Africa and Spain all use forms of PR in their legislature.24International Parliamentary Union The top ranked non-PR democracy, France, recently saw the removal of a sizeable number of incumbents by the new En Marche party of Emmanuel Macron and benefits from a system of candidate gender quotas.

Indeed at 39th in the world, the United Kingdom is currently the top ranked country in the world for number of women in its legislature to use a non-PR voting system and not to have some sort of gender quota or reserved seats for women (32%). Compare to Sweden (43.6%), South Africa (42.1%) or Spain (39.0%). At the time of writing the UK sits between Andorra and El Salvador in joint 37th and Guyana in 40th, of 193 countries whose gender balance is measured by the IPU.

Gender representation in parliaments tends to be best predicted by four variables: the presence of gender quotas or reserved seats, how many seats are won by left-of-centre parties (who tend to elect more women than right-of-centre ones), incumbency, and what political scientists call the district magnitude of the electoral system.

The district magnitude is simply a way of saying how many seats a constituency has. For instance, a British parliamentary First Past the Post constituency has a district magnitude of one, it elects a single MP. The Finnish PR constituency of Lapland, covering that province, elects seven MPs, giving it a district magnitude of seven.

The higher the district magnitude the more women and minority candidates a party will typically run. This is because in a single member constituency an electorate’s mind can drift towards what they imagine to be the ‘default’ MP – white, male, middle class. When running multiple candidates however, a party has strong incentives towards running a broader range of candidates to appeal to the broadest possible range of voters within the community.

Ultimately it is up to parties to present women candidates for election. Labour’s parliamentary group has reached 45% women, better than any other party (the second-best performer is the SNP, for whom 34% of their MPs are women). To do this, Labour has used All-Women Shortlists and the results in terms of gender representation speak for themselves. However, the difficulty of spreading this technique beyond Labour has tended to lag gender representation in parliament more widely. Other electoral systems allow for a much wider range of mechanisms to improve diversity.

Other techniques, such as candidate gender quotas (where a party must put up for election a gender balanced list), legislative quotas (where the electoral system makes sure gender representation does not fall below a certain level through its mechanics), reserved seats and the use of ‘zipping’ provide mechanisms that may be less controversial for other parties. PR is an enabler of techniques for increasing women’s representation.

Labour has used ‘zipping’, in which party lists alternate genders, to help elect more women in list elections in the UK. For this reason Labour’s group in the PR elected European parliament is 50/50, and this has helped contribute towards representation in the London Assembly (50/50) which used a mixed system, Welsh Assembly (majority women group with 52% women) and the Scottish Parliament (46%) which use proportional electoral systems.25Ljiphart, Patterns of Democracy. Verardi (2005), Electoral systems and income inequality. Zuazu (2017), Electoral Systems and Economic Inequality: A Tale of Political Equality

Inclusiveness in this way goes way beyond simple descriptive representation. A parliament that represents communities more broadly and looks more like Britain is a more empathetic parliament, more capable of considering the needs and desires of those it represents.

And this, of course, means a parliament more in tune with the diverse population unions represent.

Conclusion

The trade union movement has always been at the vanguard of political change in Britain.

Furthering social justice and the interests of workers goes hand-in-hand with political institutions that deepen political equality – rather than ones which foster alienation, and which concentrate political power in a minority of voters in a minority of seats. To ignore the role of the political system in driving political inequality is to miss the potential for radical political change.

Though the Labour government of 1997 moved the UK closer to a consensus model, Britain still lies at the extreme end of the majoritarian spectrum and this accounts for many of the cultural and structural problems in our politics.

To truly shift power closer to the people on a long-term basis requires more than changing the underlying economic structures. Embedding changes in the political system would allow for a change in the very way we do politics, securing better social and political outcomes.

There are a number of ways of getting there. Electoral reform can be part of an inspiring package of democratic reform that empowers working people and communities – moving us closer to the Chartists’ vision of a democracy for all – and of unions’ long struggle for both an economy and political system that prioritises equality over the dominance of the few.

There is growing momentum for change in the labour movement – whether it’s unions like the PCS or RMT backing reform on the union side, or individuals like John McDonnell pushing for fair votes at the top of the Labour party.

Unions and progressives have set out a vision for an economy that works for the many. That must now go hand in hand with a politics for the many.